The largest exhibition of Cezanne’s work in the UK since the 1990s was heaving with visitors, even on a weekday and despite being ticketed. That surprised me for an artist that died over a century ago.

US artist Kerry Marshall says in the exhibition book that “No one looks to nature or the self anymore, as the source of revelation in art . . .” And yet that was exactly what Cezanne did throughout his life. Initially influenced by Delacroix, Daumier and Courbet, and later Pissarro as his mentor, he countered fragmentation with attention to the organisation of his compositions, reconciling the contradictory demands of abstraction and representation.

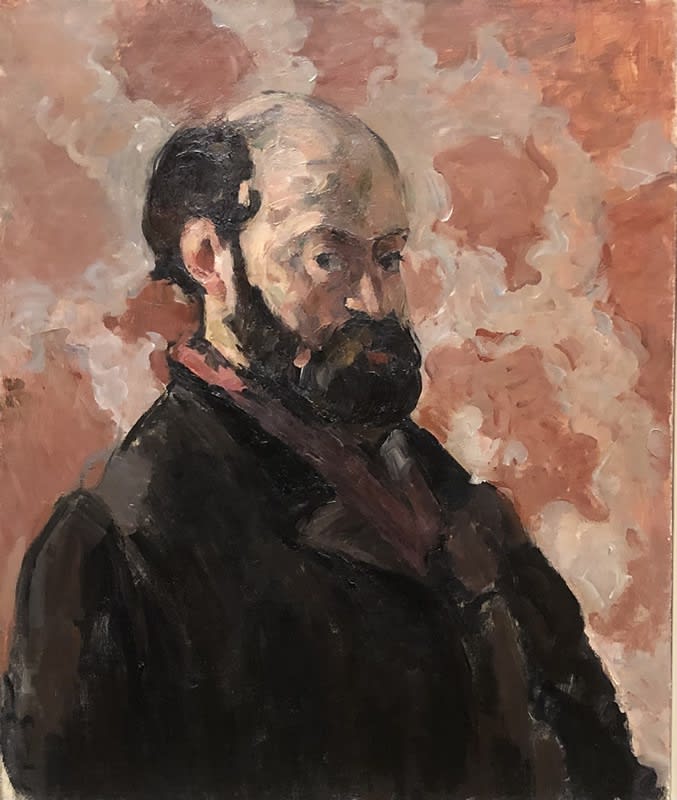

Portrait of the Artist with Pink Background

As a young artist at Camberwell School of Art where Cezanne was treated like a saint, I remember seeing a display of his early works (1859-1872), thinking this person could not draw very well. It all looked so amateurish! Of course, I was looking through the distorted lens of analytic classicism and the stiffness of so-called “correct” drawing. I was oblivious to his sensuousness, his tormented fantasies and erotic awkwardness. He told Renoir that it took him twenty years to realise that painting was not sculpting.

The Battle of Love

Cezanne was the son of a wealthy banker, lucky enough in his formative years to be best friends with the pre-eminent French author Emil Zola. His father objected to his desire to be an artist and their family relationship never appeared comfortable. Cezanne even concealed his relationship with his model Marie-Hortense Fiquet and the existence of their son Paul.

They say it takes a lifetime to develop a tiny talent to its utmost and with Cezanne, whose passion was immense, there was greatness in his talent. There was a moral weight in his exuberant violence and persistent restraint through meticulous labour. He developed a capacity for infinitesimal variation with chords of colour in his efforts to attain accuracy together with an inevitable degree of human error. This extensive exhibition provides a continuous source of interest and pleasure, the many works giving breath and life, giving a picture of his overall output.

Still Life with Apples

It is said you could buy a Cezanne painting in Pere Tanguy’s shop in 1870s Paris, a French paint dealer at the time, for as little as 40 francs. Cezanne has proved to be a great painter for the twentieth and twenty-first-century art market, with current prices topping £150 million. But the bubble of art market prices does not detract from this description of him, written in a letter to Zola by a mutual friend: “that poetic, fantastic, bacchic, erotic, antique, physical, geometrical friend of ours.”

They talk about Cezanne breaking the rules, like an anarchist, but he made his own rules and followed them in a slow, methodical and orderly manner. He wasn’t a rule-breaker. We think of him as a disciplined cerebral artist rather than the agitated, sensual, violent man he was underneath. Reconciling opposites, the conflict between classic and romantic, searching for an organic structure with the poetry of perception. Grand and quirky in the conversation between objective perception and subjective encounter as a journey into the unknown.

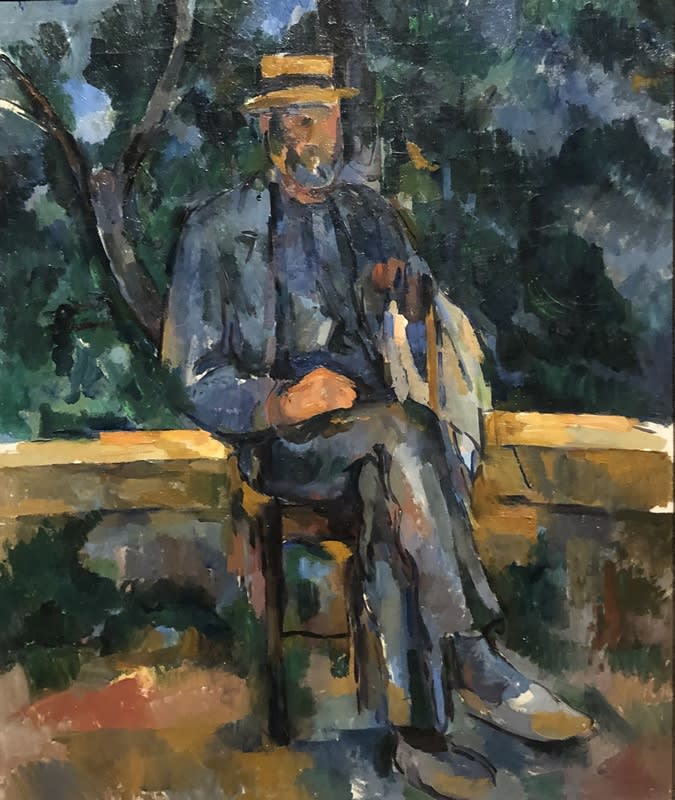

Seated Man

Cezanne studied his subject with ontological perception and his later works are like a tapestry with non-blended brush marks, not the smooth transitions you get with skillful craft painting. His earlier work is thick, oily and structural with gesture and movement, which I find attractive due to my practice. Form distortion comes from pressure within: it’s personal, not with overarching linear perspective. The perspective is a mix of additive and subtractive, reasserting the primacy of the painting as an object.

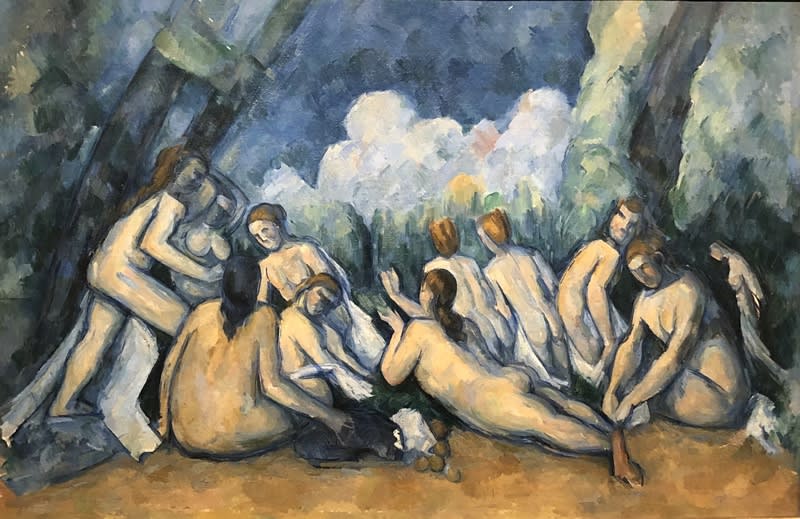

Les Grandes Baigneuses

Cezanne struggling to do what he couldn’t do rather than do what came easy. Dissatisfied with Impressionism, he was ready to pit himself against the old masters with late monumental works such as Grandes Baigneuses. Using subject matter closely he was not afraid to experiment, creating a radical new way for observation, translated into representation as a new language of reality. Cezanne wanted to be a classicist but could not – his integrity would not let him.

Mont Saints-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves

His “greatness” lies in the possibilities of future creativity that he stimulated for other artists, which were to appear in the form of Cubism, Fauvism and Expressionism. He was an exemplar who influenced successive generations of artists from both modern and contemporary eras in their search for an autonomous painting style. It was not the art market that made him great, but his life’s self-directed, single-minded movement. In his letter on 23rd October 1905 to Emile Bernard, he stated, “I owe you the truth in painting and I will tell it to you.” And that is what you sense from Cezanne, from the whole exhibition, the truth.

Article by Peter Clossick NEAC PPLG

'Cezanne' is at Tate Modern until 12 March 2023