This month, we shine the spotlight on Alex Fowler who has been a New English member since 2004. You can read his biog and view original paintings for sale on his profile page. Alex works predominantly in oils and his subjects are various: landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. We kicked off by asking him if he always wanted to be an artist...

"I always suspected that my work would involve art, but I wasn’t certain whether as a painter or in some other area of the art world. I worked at Phillips the auction house during university holidays and worked as an intern in the Prints and Drawings Department at The Art Institute of Chicago, which I loved but it was perhaps a little dry and academic for me. I wanted to bypass all the research and just spend time with paintings, talk about paintings, untangle them, pick them apart . . . and how better to do that than to make them yourself.

I had always painted. When people ask me when I became a painter, with a wry smile, I will ask them when they stopped. You don’t find many toddlers who don’t love painting!

"Art was always my favourite subject at school"

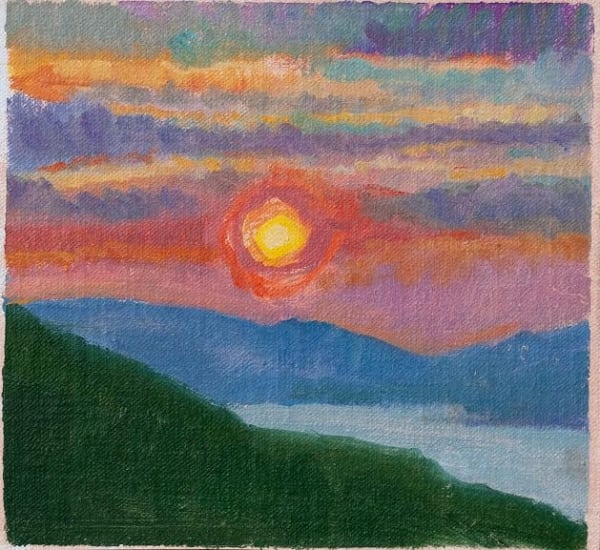

At the age of thirteen, my Godmother gave me the book ‘Modern Art: Impressionism to Post Modernism’ edited by David Britt and I found the sheer range of images so inspiring. Should I ever chance upon one of the paintings in the flesh, it feels like reconnecting with a long-lost childhood friend. Art was always my favourite subject at school; I loved leafing through art books in the school library and was very drawn to the wonderful range of art made in the 20th century, in particular the work that we might broadly describe as Expressionist: Matisse, Munch, The German Expressionists, perhaps this was a teenage thing. The woodcuts made by Die Brücke Group inspired me to make my own versions in linocuts. I think the limitations of the medium forced me to distil images into simplified shapes and colours – you can’t overwork a linocut like you can a painting. I sometimes have to remind myself when painting to think like a printmaker and not fiddle around making minute adjustments. In recent landscape paintings of the changing light, painting the magic hour in Montenegro [more on that later . . . ] this has been of primary concern.

After school, I did a foundation course at Chelsea College of Art. I had a great year, though I did very little painting. I made funny little abstract sculptures out of wire, wood and plaster. It was a year of experimenting, discovering the arena of contemporary art, and playing a lot of football in the courtyard! I had always thought that I would most likely do an academic degree at university, as at that point I was uncertain whether my future lay in being an artist or getting a job in the art world. I ended up going up to Edinburgh to study Art History.

I kept up painting at university and it was at that time I got my first commission. A friend’s Mum asked me to paint my friend’s portrait on the occasion of her 18th birthday. I made it from a photograph but really enjoyed it. It felt very grown up to have a commission, though I am not sure I was particularly qualified then! I was paid £100, which felt like an awful lot of money at the time and a couple of years later, I painted her younger brother too.

At that point, portrait painting seemed like a sensible way to make a career out of painting and I was recommended the two-year Portrait Diploma at the Heatherley School of Fine Art.

Studying at Heatherleys

I loved my time there. Except for the odd self-portrait or drawing of a friend, I had never painted the figure from life before. At Heatherleys the model would pose for about six days. A different tutor would teach each project, so we would have a wonderful range of different setups through the two years. I remember painting a nude lying on a great expanse of sky blue, which threw all kinds of beautiful reflections into the skin. Often we’d have models simply dressed to focus the eye on the head, but sometimes the set up would be a riot of pattern. I remember models dressed in wonderful silk dressing gowns and set against highly elaborate patterns daring us to include everything.

On influence and taking criticism:

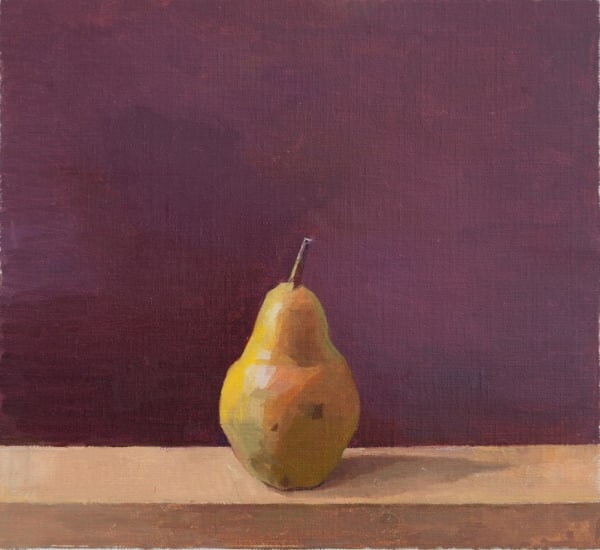

I remember David Woodcock was the first to introduce me to the work of Euan Uglow and to the idea of building up a painting with related patches of colour. After my first day’s work, he told me that it looked like I had emptied a packet of Smarties onto my canvas. Of all the comment by any tutor at art school, it is the one I recall best. I am so glad he didn’t pull his punches and gave me an honest assessment because, over time, I began to realise that subtle relationships of colour shapes could stand for the form and that these opaque blocks of colours, when placed in the right arrangement, could sing like beautiful precise notes in music. It was a revelation to me and is probably the core tenet of my work.

I admire the fact that the teachers at Heatherleys didn’t present us with a pre-conceived method of painting, but instead encouraged us to engage with questions of how we experienced the visible world through perception and feeling, and how we might respond to it in a meaningful way. When the act of painting feels like an enquiry suffused with possibility the enterprise is tremendously exciting.

It was at Heatherleys that I met Karn Holly. She was a wonderful teacher and painter and a greatly missed member of the New English. I had never come across anyone like Karn before. She would teach through metaphor, employing language from poetry and music to shake us out of seeing like the man at the bus stop as she put it! The metaphors were sometimes surprising. If the space in a drawing wasn’t working she might tell you to hit the baseline, bringing to bear in painting our experience of the dynamics of a tennis match. Then she’d be talking about ‘vibrato’, how a passage in a painting might demand just the right weight of scribble, always meant, never sketchy. She’d have us draw the model up close or from a great distance observed through a polo mint hanging from the ceiling, anything to shake us out of our habits of looking.

"The camaraderie of the New English"

Towards the end of my final year at Heatherleys, on Karn’s suggestion, I applied and was awarded The Drawing Scholarship at the New English Art Club. It was my first encounter with the society. Two years later, in 2004, I was fortunate to be elected as a member. Painting can be a lonely business and so the camaraderie of the New English is invaluable. I always look forward tremendously to the Annual Exhibition and a chance to see old friends. It is a great honour to show alongside so many wonderful painters.

One of the great benefits of being London based is the proximity of the galleries and museums, so much great art. I always remember Bridget Riley’s advice in her wonderful collection of writings 'The Eye’s Mind' to stand on the shoulders of the giants, advice not always given at art schools today where some tutors place all the emphasis on originality at the expense of developing skill and understanding and then, gradually, one’s own voice.

Great paintings don’t always reveal their mechanics clearly. They are too perfect. That is why drawing or painting a transcription of a painting is such a valuable lesson. You can learn a great deal about why the painting works as your own version evolves and the parts start to click into place. That a colour for a particular passage, a cheek in shadow say, might look completely different from the palette to the painting is one of the great revelations a student of painting can experience.

During the process of painting, the artist can step back at any point and view their work as if it were finished. They are always in the role of the viewer. The beauty of a painting is that you can take it in in a few seconds. It hits you, boom, a visceral experience. That you can watch it evolve in front of your eyes is one of the fascinations of being a painter, but of course, it can be terribly frustrating too if a painting isn’t working and you can’t figure out why.

As for criticism. If I really believe in a painting I tend not to worry about criticism. Often it is just a matter of personal taste. In the outside world, people are rarely critical to your face about your work, but an honest critique of a painting from someone you admire can be very valuable – however experienced we are.

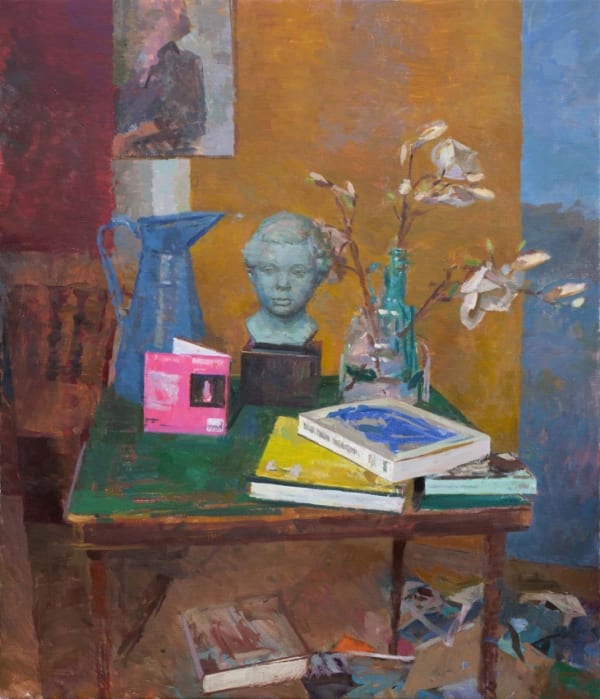

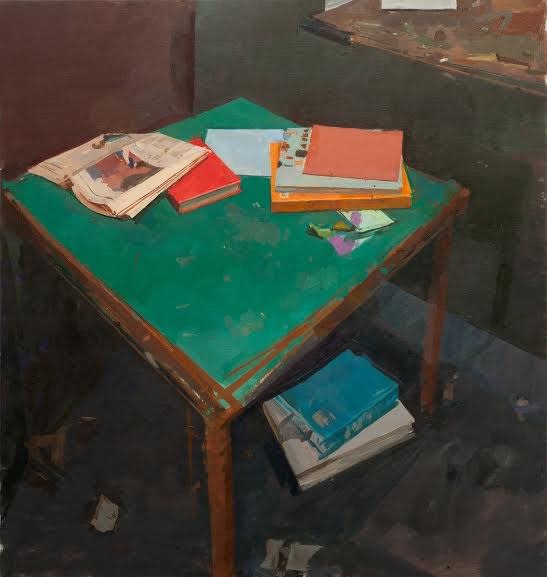

Sometimes, I won’t realise if I have done something good. About ten years ago, an ex-tutor of mine Allan Ramsey visited my studio and saw the first of my card table paintings. It was a bit of a departure for me, the objects were so simple that the geometry and colour became the crux of the work, but was it strong enough. Allan’s responded to it so positively which reaffirmed my own gut sense that it was a strong painting. It gave me the confidence to recognise how much the painting really resonated with me. Its sparse and abbreviated qualities were perhaps its strength. The card table has become a regular element in my work ever since.

Back to Montenegro . . .

Outside of portrait commissions, I have mainly been working on small paintings recently. I was out in Montenegro teaching and painting and found myself incredibly excited about painting the sunset. There are few visual phenomena more beautiful and surprising than the extraordinary array of colours and shapes produced in that magic hour. You never know what the sky will do. You are forced to simplify the scene into a few essential colour relationships shifting the tonal range up and down the scale to accommodate the most intense hues. I often make about six mixtures before I begin painting, mixing with the palette knife. It forces me to break down the subject into the key colour shapes, all conceived in relation to each other. But then it is about chasing a sense of rightness. The painting may go through numerous transformations as marks accrue in response to the changes in the scene.

On materials:

When painting abroad, I tend to travel with a roll of pre-primed acrylic canvas that I will cut into pieces to be stretched or glued to board when I return home. I stick it to the board with white gaffer tape. On occasion, I will experiment with a pre-applied wash or ground - a pale orange or pink. I use a wide range of colours from the tube to represent as much of the spectrum as possible: Titanium White, Cadmium Lemon, Cadmium Yellow, Cadmium Yellow Deep, Cadmium Orange, Cadmium Red Light, Brilliant Pink, Cadmium Red or Red Deep, Quinacridone Rose, Alizarin Crimson, Burnt Umber, Raw Umber, Ultramarine Blue, Cerulean Blue, Cobalt Teal and Phthalocyanine Blue. The certainly don’t all crop up in every painting but they are in my paintbox if I need them.

A favourite work?

I am not sure I have a favourite, perhaps my painting of Greenwich Street, San Francisco [see image below]. The basis for the painting was a study on the spot, supplemented by photographs primarily to aid with the topography. The painting loomed large in my little studio. I was trying to crank everything up: the intensity and range in the colour and the mark making. Once the relationships started to work and the feeling of intense Californian light started to occur it took me right back to being on the spot painting the study. It was a rare and marvellous experience."

Find out more about Alex on his artist profile page where you will also find a selection of original paintings for sale.